Common Objections to DevOps from Enterprise Operations

Alex Honor /

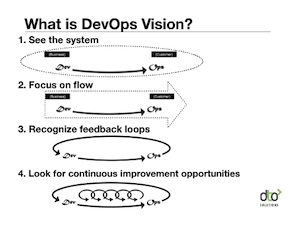

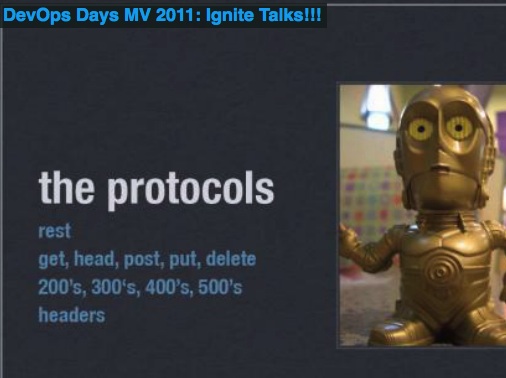

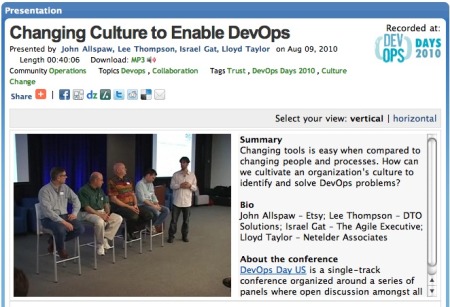

I’ve been in many large enterprise companies helping them learn about devops, helping them understand how to improve their service delivery capability. These companies have heard about devops and are looking for help creating a strategy to adopt devops principles because they need better time to market and higher quality. Not everyone in the company believes in devops for different reasons. To some, devops sounds like a free for all where devs make production changes. To others devops sounds like a bunch of nice sounding high ideals or that devops can’t be adopted because the necessary automation tooling does not exist for their domain.

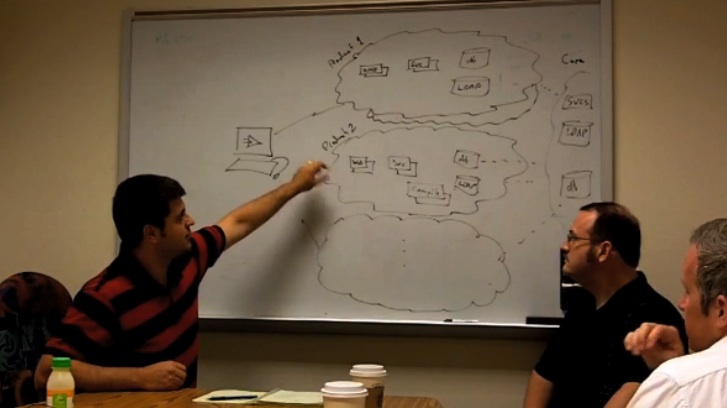

In the enterprise, the operations group is often centralized and supports many different application groups. When it comes to site availability, the buck stops with ops. If there is a performance problem, outage or issue, the ops team is the first line of defense, sometimes escalating issues back to the application team for bug fixes or for help diagnosing a problem.

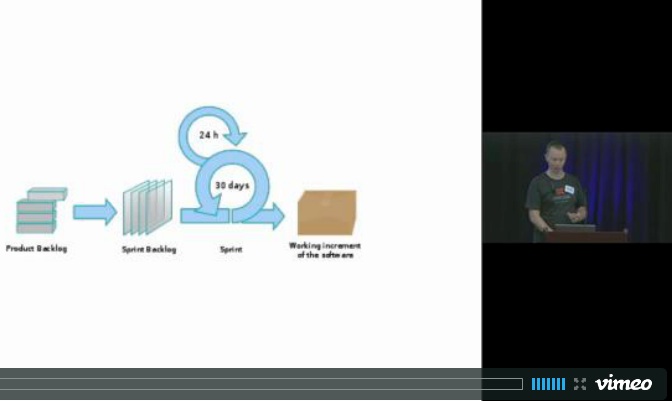

Enterprises interested in devops are also usually practicing or adopting agile methodology in which case demands on ops happen more often, during sprints (e.g., to set up a test environment) or after a sprint when ops needs to release software to the production site. The quickened pace puts a lot more pressure on the centralized ops team because they often get the work late in the project cycle (i.e., when it’s time to release to production). Because of time pressure or because they are over worked, operations teams have difficulty turning requested work around and begin to hear developers want to do things for themselves. Those users might want to rebuild servers, get shell access, install software, run commands and scripts, provision VMs, modify network ACLs, update load balancers, etc. These users essentially want to do things for themselves and might feel like the centralized ops team needs to get out of their way.

How does the ops team, historically the one responsible for uptime in the production environment, permit or expand access to environments they support? How can they avoid being the bottleneck at the tail end of every application team’s project cycle? How does the business remove the friction but not invite chaos, outages and lack of compliance?

If you’re in this kind of enterprise environment, how do you start approaching devops? If you are a centralized operations team facing the pressure to adopt devops, here are some questions and concerns for the organization to ask or think about. The answer to these questions are important steps to forming your devops strategy.

How does a centralized group handle the work that needs to be done to make applications run in production or across other environments?

For some enterprises, they begin by creating a specialized team called “devops” whose purpose is to solve “devops problems”. Generally, this means making things more operations friendly. This kind of team might also be the group that takes the hand off from application development teams and wrap their software in automation tooling, deploy it, and hand it off to the Site Reliability team. Unfortunately, a centralized devops team can become a silo and suffer from the same “late in the cycle” handoff challenges the traditional ops group sees. Also, there is always more developers and development projects than there can be devops engineers and devops team bandwidth. A centralized devops team can end up facing the same pressures as a traditional QA department does when they try “adding quality testing” as a separate process stage.

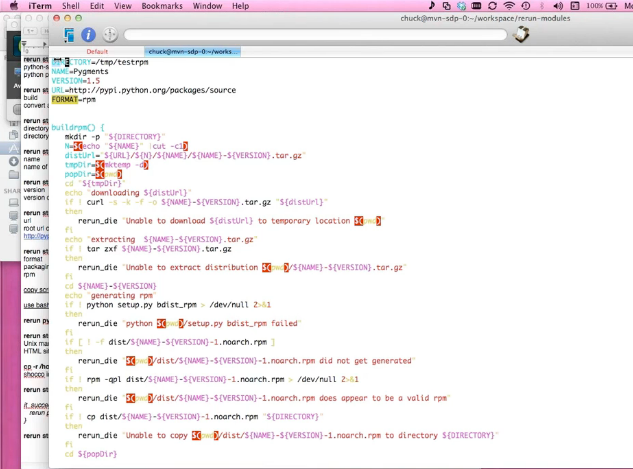

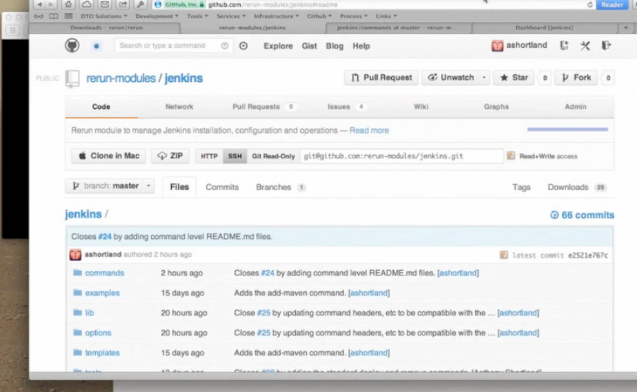

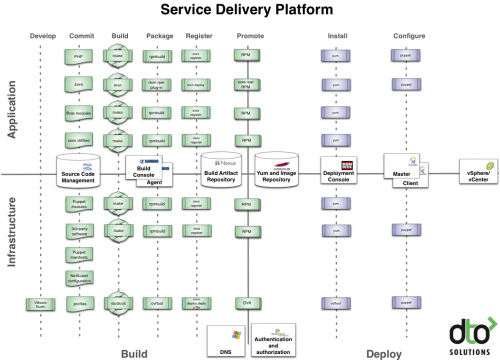

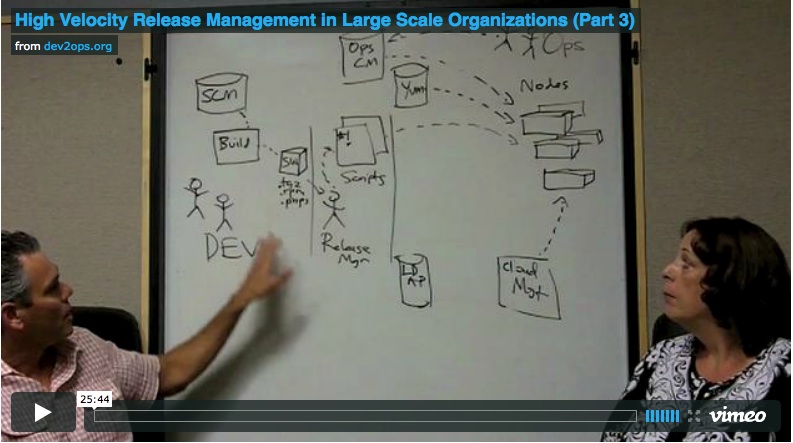

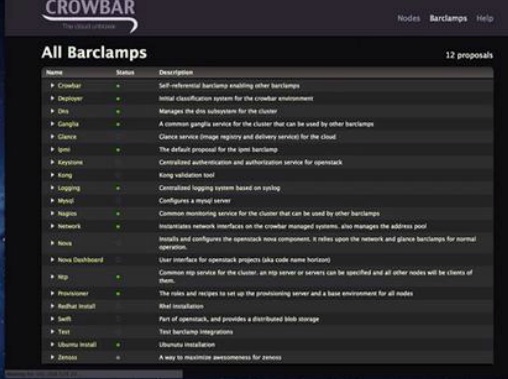

To make sure an application operates well in production and across other environments the devops concerns must be baked into the application architecture. This means the work to make applications easy to configure, deploy and monitor is done inside the development stage. The centralized operations group must then learn to develop a shared software delivery process and tool chain. It’s inside the delivery tool chain where the work gets distributed across teams. The centralized ops group can support the tool chain like architects and service providers providing the application development teams a framework and scaffolding to populate the needed artifacts to drive their pipeline.

What about our compliance policies?

Most enterprises abide by a change policy that dictates who can make production changes. Many times this policy is interpreted to mean anybody outside of ops is not allowed to push changes. Software must be handed off to an ops person to push the change. This handoff can introduce extra lead time and possibly errors due to lack of information.

These compliance rules are defined by the business and many times people on the delivery end have never actually read the language of these policies and base process on assumptions or their beliefs formed by tribal knowledge. Over time, tools and processes can morph in arcane ways, twisting into inefficent bureaucracy.

It’s common to find different compliance rules apply depending on the application or customer type. When thinking about how to reduce delivery cycle time, these differences should be taken into account because there might be alternative ways for seeing who and how change can be made.

Besides understanding the compliance rules, it should also be simple and fast to audit your compliance.

This means make it easy to find out:

- who made the change and were they authorized

- where the change was applied

- what change was made and is it acceptable

This kind of query should be instantly accessible and not something done through manual evidence gathering long after the fact (e.g., when something went wrong). Knowing how change was made to an environment should be as visible as seeing a report that shows how busy your servers were in the last 24 hours.

These audit views should contain infrastructure and artifact information because both development and operations people want to know about their environments in software and server terms. A change ticket with a bunch of verbiage and bug links does not paint a complete enough picture.

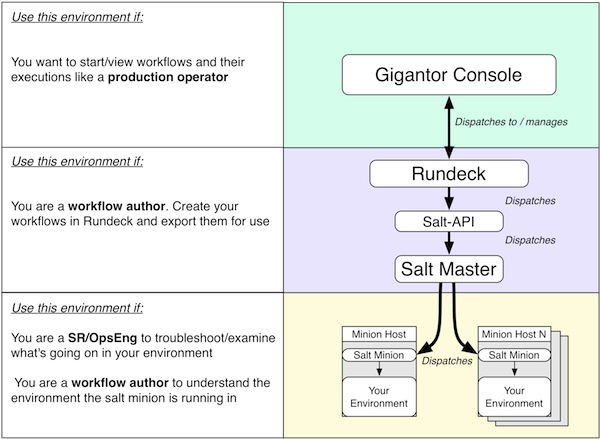

How do you open access but not lose controls?

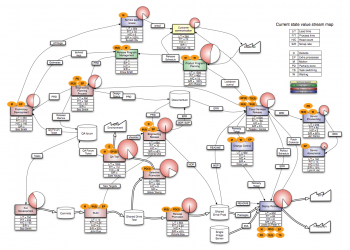

After walking through a software delivery process it’s easy to see the flow of work slows anytime the work must be done by a single team that is already past their capacity and is losing effectiveness due to context switching between competing priorities. This is the situation an ops team often finds itself. Ops teams balance work that comes from application development teams (e.g., participate in agile dev sprints), network operations (e.g., handling outages and production issues), business users (e.g., gathering info for compliance, asset info for finance) and finally, their own project work to maintain or improve infrastructure.

To free this process bottleneck the organization must figure out how the work can be redistributed or can be satisified by some self service function. Since deployment, configuration and monitoring are ops concerns that should be designed into the application, distribute this development to the developers. This can really be a collaboration where ops maintains a base set of automation modules and give developers ways to extend it. Create a development environment and tooling that lets developers integrate their changes into this ops framework in their own project sandboxes.

Provide developer access to create hosted environments easily through a self service interface that spins up the VMs or containers and lets them test the ops management code.

Build the compliance auditing logs into the ops management framework so you can track what resources are being created and used. This is important if resource conflicts occur and let you learn where more sandboxing is needed or where more fine grained configuration should be defined.

Moving faster leads to less quality, right?

To the business, moving fast is critical to staying competitive by increasing their velocity of innovation. This need to quicken the software delivery pace is almost always the chief motivation to adopt devops practices.

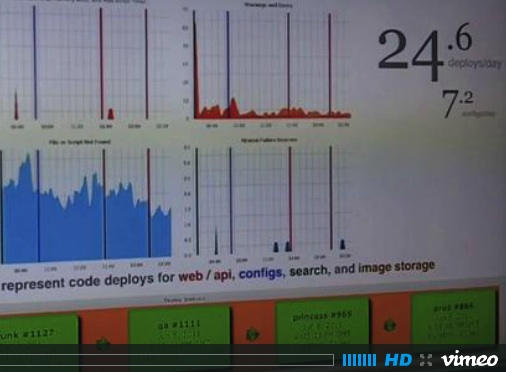

Devops success stories often begin with how many times deployments are done a day. Ten deploys a day, 1000 deploys a day. To an enterprise these metrics can sound mythical. Some enterprises struggle to make one deploy a month and I have seen some enterprises making major releases on an annual basis and the rollout of this release to their customers taking over 30 days. That’s thirty days of lag time and puts the production environment in an inconsistent state making it hard for everyone to cope with production issues. “Is it the new version or the old version causing this yet unidentified issue?” A primary reason operations is reluctant to move faster is due to the problems that occur during or after a change had been made.

When change leads to problems these are typical outcomes:

- More control process is added (more approval gates, shorter change windows)

- Change batches get bigger (cram more work into the given change window)

- Increase in “emergency fixes” (high priority features get fast tracked to avoid the normal change process)

- High pressure to make application changes quickly results in patching systems and not through the normal software release cycle.

Given these outcomes the idea of moving faster is crazy because obviously it will lead to breaking more stuff more often.

The question is how do organizations learn to be good at making change to their systems? Firstly, it is helpful to think about what kind of safety practices are important to move change. Moving fast means being able to safely change things fast. Here are some general strategies to consider:

Small batches

Large batches of change require more people on hand due to the volume of work and the work can take longer to get done.

The solution is to push less change through so it’s easier to get it done and have less to check and verify when the change is completed.

Rehearsal

Here’s a good mantra, “Don’t practice until you get it right. Practice until you can’t get it wrong.” Don’t make the production change be the first time you have tried it this way. Your change should have been verified multiple times in non production environments before you tried it in production. Don’t rely on luck. Expect failure.

Verifiable process stages

Whether it is a site build out or an update to an existing application, be sure you have well defined checks for your preconditions. This means if you are deploying an application you have a scripted test that confirms your external or environment dependencies before you do the deployment. If you are building a site, be sure you have confirmed the hardware and network environment before you install the operating platform. Building this kind of automated testing at process stage boundaries adds a huge deal of safety by not letting problems slip down stream. You can use these verification checks to decide to “stop the line”.

Process discipline

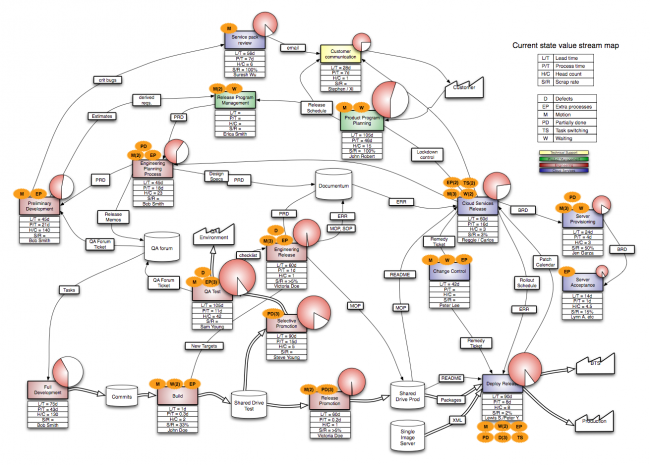

What leads to places full of snow flake environments, each full of idiosyncratic, specially customized servers and networks? Lack of discipline. If the organization does not manage change consistently together, everyone ends up doing things their own way. How do you know you have process discipline? Look for how much variation you see. If process differs between environments, that is a variation. Snow flake servers are the symptoms of process variation. Process variation means you don’t have process under control. There are two simple metrics to understand how much control you have over your process: lead time and scrap rate. Lead time is how long it takes you to make the change. Scrap rate is how often the change must be reworked to make it right. Rehersal and verifiable process stages will help you bring process under control by reducing scrap rate and stabilizing lead time. The biggest benefit to process discipline is improving your ability to deliver change predictably. The business depends on predictability. With predictability the business can guage how fast or slow it can move.

More access into ops managed environments?

The better everyone understands how things perform in production the better the organization can design their systems to support operations. Making it hard for developers or testers to see how the service is running only delays improvements that benefit the customer and reduces pressure on operations. It should be easy for anyone to know what version of applications are deployed on what hosts, the host configuration and the performance of the application.

Sometimes data privacy rules make accessing data less straightforward. Some logs contain customer data and regulations might restrict access to only limited users. Instead of saying no or making the data collection and scrubbing process manual, make this data available as an automated self service so developers or auditors can get it for themselves.

Visibility into the production environment is crucial for developers to make their environments production-like. Modeling the development and test envrionment so that it resembles production is another example of reducing variabilty and bringing process under control.

Does this mean shell access for devs?

This question is sometimes the worst one for a traditional enterprise ops team. Often times the question is a symptom of another problem. Why does a dev want shell access to an environment operations is supporting? In a development or early test envrionment shell access might be needed to experiment with developing deployment and configuration code. This is a valid reason for shell access.

Is this request for shell access in a staging or production environment? Requests for shell access could be a sign of ad hoc change methods and undermine the stability of an environment. It’s important that change methods are encapsulated in the automation.

Fundamentally, shell access to live operational environments is a question about risk and trust.

The list doesn’t stop here, but these are the most common questions and concerns I hear. Feel free to share your experiences in the comments below.