Part 1: Putting a metrics/KPI program into place in 6 steps

Walk into any web-based business and more likely than not you’ll find all sorts of metrics that have been collected with varying levels of accuracy, consistency, and freshness. However, despite what appears to be a wealth of data, no one will seem to be all that happy with it.

The frontline guys are grumbling about having to deal with the collection and reporting overhead while questioning under their breathe “what’s in it for me?”. The technology managers are still making decisions based on anecdotal evidence, gut feelings, or knee-jerk reactions to the latest incidents. And to top it all off, the business managers are clamoring for new dashboards because the last ones didn’t tell them much that was actually useful for managing the business.

In short, there is endless data floating around, but no one appears to have the knowledge they want.

Invariably another “metrics project” is going to come down the project pipeline. But why would this effort turn out any different than the previous efforts?

Here are six straightforward steps for putting into place a metrics program that actually delivers knowledge about your operations and your business:

Step #0: Stop looking for metrics and start thinking about KPIs

Most metrics projects that are initiated within a technology organization will take a bottom up view of the world. The thought process is often to grab as much data as possible and then try later to make some sense of it with a bit of analytical magic. The dream is that, with enough technical mojo, you’ll arrive at a magical “ah ha!” moment where a piece of important knowledge jumps out.

Unfortunately, for as common as this dream is, it rarely comes true. After considerable effort, these bottom up metrics projects usually result in an outcome somewhere between a mix of interesting (but not meaningful) trivia or a loss of interest in the project alltogether.

To ensure success, you’ve got to turn your technology-centric view of this problem on its head. Since the role of IT is to support the goals of the business, it logically follows that what you really want to measure is the performance of your IT operations in supporting those business goals. This is done by developing and tracking a set of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) that align the performance of your IT operations with the performance of your business

What’s the difference between metrics and KPIs? The following list is the best explanation I’ve seen on how to tell if a metric (or set of metrics) qualifies as a KPI :

- A KPI echoes organizational goals

- A KPI is decided by management

- A KPI provides context

- A KPI creates meaning on all organizational levels

- A KPI is based on legitimate data

- A KPI is easy to understand

- A KPI leads to action!

KPIs, by their very nature, are about influencing actions. If a metric isn’t capable of influencing the behavior of your team in a way that would be clearly understood from all directions, then it’s not a KPI.

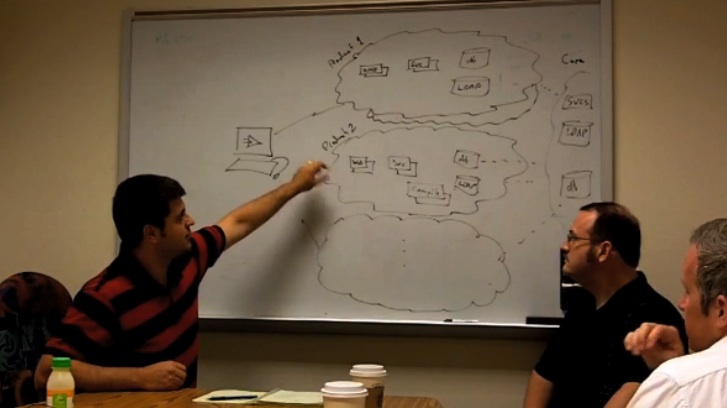

Step #1: Set up a KPI Advisory Board

KPIs, like all metrics, have little value in isolation. What’s the best way to ensure that your KPIs are going to be successful in measuring and influencing the performance of your organization? Get all of the various stakeholders involved early and often.

As your very first step, create a KPI Advisory Board that is comprised of key stakeholders from each part of your organization (Dev, Ops, QA, Business/Product Management, Finance, etc). The KPI Advisory Board is responsible for validating/updating your KPI choices, overseeing data collection, analyzing results, and relaying results to the rest of the organization. The KPI Advisory Board also helps to keep everyone honest and avoid intentional or unintentional gaming of the KPI process. Make sure the KPI Advisory Board meets on a regularly scheduled basis. Don’t overload the meetings with other issues like architecture or budgeting. Stay focused on organizational and process performance. If the KPI Advisory Board is a burden on anyone, it’s probably not being run correctly.

Due to the human dynamics involved with assembling a KPI Advisory Board, may technologists feel compelled to skip this step. DON’T. The KPI Advisory Board is essential to the success of your KPI program. Reaching consensus on what to measure and how to measure it is as important to the health of an organization as the actual measurement.

Step #2: Prioritize what is important for your business

First, get a good understanding of how business performance is measured within your company. Every business should already know what indicates good business performance in their specific case. Every business should also know what it’s strategic goals are. Ask around if you don’t know. Better yet, if you’ve formed your KPI Board correctly, those answers will come to you via the members from other parts of your organization. Be sure to take note of the priority/weighting of each goal (this will sometimes vary depending on who you asked).

Next, create a list of the ways that IT operations can impact/support each of those business goals. Your specific list will obviously depend on your business’s specific goals. However, you’ll likely find that there are four general buckets of IT operations objectives that can be mapped to your business’s goals (I’ll dig into each of these in a future post):

- Improve resource utilization/efficiency

- Decrease failure rates

- Improve operations throughput

- Enable business agility

What you should now have is a list of specific IT operations objectives mapped to prioritized business goals.

Side note: Beware of falling into the trap of thinking that what matters to the individual members of your technology team is the same as what matters to the business. Sure, less individual headaches is a good thing because headaches are generally a sign of larger systemic issues. But your business representatives on the KPI board should push back and remind you that solving your individual headaches many not be an important factor in the success of the business (and therefore not a KPI priority).

Step #3: Weight possible KPIs against your prioritized IT operations objectives

Work your way through the list of IT operations objectives and list out all of the possible candidate KPIs for each objective. Be sure to cast a broad net. Look through old metrics projects. Ask around your organization (“How would you measure…?”). Look at what others have published (“Google is your friend”).

I’ve found that it handy to keep Douglas Hubbard’s “Four Useful Measurement Assumptions” in mind when searching for candidate KPIs:

- Your problem is not as unique as you think

- You have more data than you think

- You need less data than you think

- There is a useful measurement that is much simpler than you think

Most importantly, you need to continuously ask the question “Is this really important?”. Just because something is interesting doesn’t mean it’s valuable.

Go through the list with your KPI Advisory Board. Weight the effectiveness of each candidate KPI for indicating the success/failure of each prioritized IT operations objective. Also, be sure to weight the “difficulty of measurement” for each candidate KPI. While you will ultimately be concerned with a KPIs ability to indicate progress towards meeting goals, understanding the “difficulty of measurement” can have practical implications when deciding where to focus first.

Step #4: Gain consensus on a manageable set of KPIs

Work first within the KPI Advisory Board and then across your broader organization to gain consensus on a manageable set of initial KPIs. I’d recommend that your start with no more than 5 – 10 KPIs. Keep it simple. Get the win.

To select your initial set of KPIs use the weighting and prioritization determined in the previous steps. More often than not, you’ll be surprised at what candidate KPIs come out on top of the list. Of course a bit of gut feeling and pragmatism may come into play, but try to trust the prioritization process. If company politics or strong interpersonal dynamics get in the way, try your best to still reach consensus (but stay focused on getting something done). Your initial goal should be to gain experience with the process and to achieve early success that the organization can buy into. You can always expand and/or refocus later.

Step #5: Baseline and track

Create a baseline for each of the initial KPIs you’ve selected. This is also a good time to validate any of the assumptions you’ve made in the previous steps.

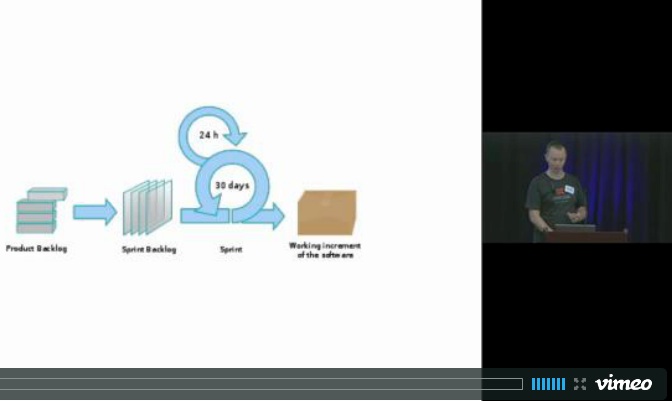

If everything looks reasonable, begin regular tracking of the initial set of KPIs. It’s best to start with manual (or semi-manual) data collection and KPI reporting. If you jump straight for a tool you are going to get caught up in what can/can’t be automated and what the right way is to go about that automation. This will just distract from what you are really trying to figure out… are we tracking the right thing and does the output make sense?

Transparency is an important issue in this process. Make sure that anyone with a reasonable understanding of your operations is able to understand how and why these KPIs indicate success/failure (e.g. “Can the CEO/CFO make sense of this?”)

Step #6: Re-evaluate and expand

Your KPI Advisory Board should meet on a regular basis to validate/analyze results and propose new KPIs (if any). Initially these KPI Advisory Board meetings should be held weekly. However, over time, monthly KPI Advisory Board meetings (with weekly or daily distribution of KPI reports) will usually be sufficient.

Also, this is the point where you should start investing in automating the data collection and KPI reporting. Once you get a few cycles under your belt, you’ll have an understanding of what needs to be measured and how it should to be measured. And perhaps more importantly, you should have earned the buy-in and budget approval needed to get automated data collection and KPI reporting done correctly. Automation will ultimately allow you to track more KPIs (not always a good thing) with a higher degree of accuracy (a good thing) and provide a quicker feedback loop for your organization (always a good thing).

How difficult is it to implement a KPI program?

This is a common question. My consulting company helps companies accelerate the building of their KPI capabilities. We’ve got a mature methodology (based on the steps above). We use decision modeling tools built by partners. We use proven practices for building consensus and extracting analysis. We get our clients to a mature process as quickly as possible. Next to an example like that this may seem overwhelming to tackle on your own, but it’s really not.

KPI programs might be difficult to perfect, but they are easy to start. Start small, focus on building consensus, and grow iteratively. Since all businesses are dynamic, refining your KPI capabilities is more important than any one measurement.

Go to Part 2 in this series –>