Being a consultant I get a wide exposure to real life dev2ops experiences at both large and small companies and usually get called in the aftermath of a bad deployment. Businesses of course accomplish dev2ops in their own ways but run into trouble as their applications and operations become more complicated. I always like to start by listening to the key dev2ops individuals to get the story from the person on the ground. These key dev2ops guys recount something like this:

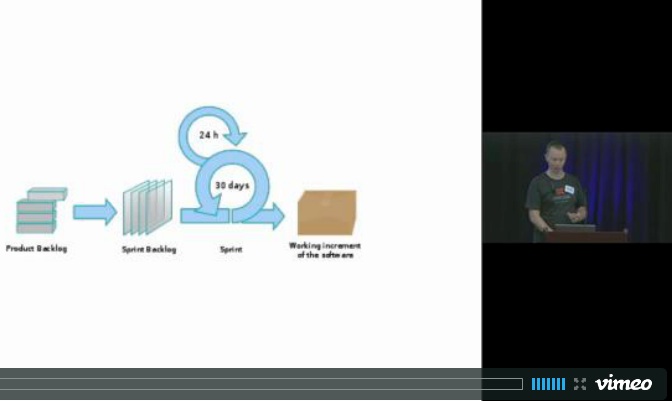

The big application upgrade was scheduled for 8pm but ended up being at 11, due to some last minute bugs found in QA. After the fixes were committed to the version control system, new software builds were created. These builds were a bit different from what had been discussed in the pre-deployment planning meetings. They also included some new configuration rules and relied on some manual tweaks outside of the normal procedure.

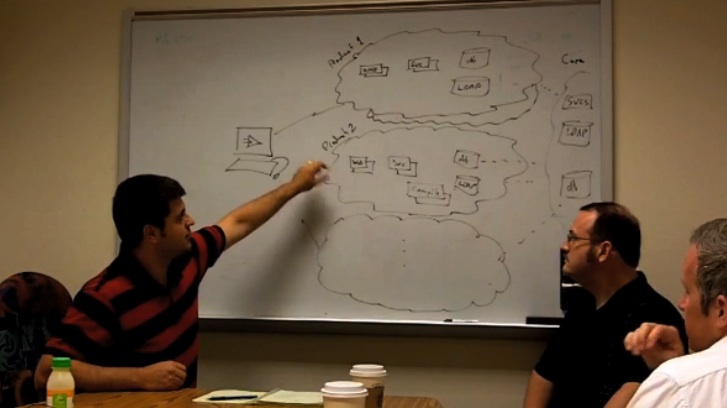

Last minute changes were understandable, since the development team was rushing to meet a project deadline and had been working within an aggressive and compressed time frame. Unit development had been moving along steadily but the last stage integrations were problematic and relied on senior developers to work out kinks in order to get the necessary disparate builds working in QA.

By 12am, the production updates were well underway. There are a lot of machines and files to distribute to them, along with various system commands that need to be run. The normal update process is semi-automated but still very intensive. One must be very careful when performing these updates — one misstep can slow down the whole upgrade process. After all the binary packages were installed, and SQL scripts executed, manual tweaks performed, all parts of the application were restarted to bring the whole site to use the new code and configuration. Subsequent testing of the application uncovered that some new features did not work. The cause was not apparent and suggested faulty application code. A key developer diagnosed the issue, finding the hastily written manual procedures missed a few configuration file changes. The missed edits were applied, the application was restarted again and this time testing confirmed all new features were working. By 2am, all user load was directed to the general production environment, and everybody involved with the upgrade went home. The night shift in operations would monitor the application and let everyone know if any issues arose.

At 7am, users started logging into the application and began conducting transactions. As more logged in, random errors began to occur. Users begun reporting error messages in their web browsers. Operations noticed load spiking on the production machines. The application’s quality of service continued to deteriorate to the point where the problem was escalated to the key individuals involved during the night deployment.

By 7:30am, operations was troubleshooting the problem within the system and network layers while development was logged into several production machines looking at application log files. At 8am, the whole application appeared to degrade into a giant, unresponsive CPU and network consuming monster. System administrators observed full process tables. Network admins discovered unresponsive ports. Developers read off application stack traces. All able hands on deck were requested to join a bridge conference call and visibility of the problem had made its way to the “C” level management ranks. Everyone began asking each other what might be the root cause. Was it a change in the new software or some other possibly unrelated change?

The development group was not the only busy team during that past few weeks. The operations team was making various updates to the infrastructure, some in preparation for the big application update, others for good proactive maintenance. These changes — new firewall rules, operating system updates, security patches, and web server configurations — were scheduled and implemented at different times and none had a negative impact. But, each one would now be suspect.

At 9am, system administrators and developers were logged into production machines, furiously hacking configuration files, undoing bits and pieces of the new application, and restarting the application’s server processes. Caution was thrown to the wind, as those attempting to resolve the problem made ever more daring steps to restore service. Application response sporadically improved but the whole system did not become stable.

Finally, at 9:30 management makes a dreaded yet inevitable call: back out the new application code and bring the site back to how it worked the day before. Naturally, everyone was reluctant to attempt reverting back to the old versions because it’s a tricky and intensive procedure under normal circumstances. On the other hand, application quality of service was so bad, what would be the real user impact?

Around noon, after two and a half hours of mammoth effort, the whole production environment was running on the old versions and the site was operating normally. 5 hours of business service had been interrupted. Postmortem meetings held by management revealed that the planned upgrade was affected by an incompatibility between a newly patched system library applied to production machines that differed from what is used in development and QA machines. Further, during the troubleshooting, someone discovered that several machines appeared to have incorrect configuration files. Finally, the analysis highlighted that backing out an application change was extremely difficult, error prone and took much too long.

I have heard this kind of story at big and small companies by people that subscribe to formal methodologies and from those that eschew them. Sometimes the severity and scope of the problems vary, some cases there is little to no user impact while others it’s a total site outage.

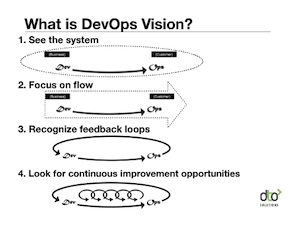

Anyone that has experienced a nightmare like this knows it is quite hair raising, a good cause of burnout and certainly tests the morale and team play in any IT organization. Reflecting on the chain of events, one realizes that the problem does not just boil down to a lack of project management, administrative policy, nor technology. But, there is an obvious lack of coordination, coordination in the most general sense. How an IT organization aligns itself to directly support the dev2ops process certainly is a factor in avoiding deployment nightmares.